Say it’s about art and trash. When the asker replies, “You mean, like, garbage?” Say, “Yes, and also…”

Express that your work draws on memoir and art criticism, that it uses art as a prism through which to refract your experience, to draw out its colors into neat, organized arcs.

Delight in the fact that your publisher has gifted you the services of a publicist, a person who will help you market and sell your book. Over email, he mentions the copy you wrote to accompany the book in press materials. He would like to know if you have considered that it sucks. You have considered it. The publicist would like to discuss or think about discussing revising your awful copy. So that people will know what the book is about.

When you say the book is about growing up white trash, the asker usually stares at you blankly. They are afraid, perhaps, to acknowledge that they know this term. In the past, they may have used it in an unflattering way. Or maybe it is, to them, a slur too terrible to mention. You smile at their flat faces, then soothe them by saying you are complicating the insult, suffusing it with endearment. “Oh,” they reply. “Okay.”

If you really don’t want to talk about it, say it is a book of experimental art criticism. It contains performance art instructions that ask the reader to enact the ideas presented in the essays through a physical interaction with trash. These are called rituals. There are also some of your collages in it. Say the book contains several very long essays about some art you find interesting, chiefly because of its relationship to garbage.

Another way to explain what a book is about is to say what it’s not. Your book is not a best-selling novel. You are not Sally Rooney or Jonathan Franzen, nor will you ever be.

The asker will sometimes offer a title to test their understanding of what the book is about. A few will ask if it is like J.D. Vance’s memoir Hillbilly Elegy. Even though both books have poor people in them, they really have nothing in common.

Another thing the book is not: a memoir.

The publicist insists that you call the book a memoir. When you edit your promotional copy, he needs you to summarize the book’s narrative arc. He wants adjectives. You do not think the book has a narrative arc because it is not a narrative, but rather a collection of ideas, anecdotes, and observations. The essays are rangy, thoughtful, and inventive. You are defying conventional categorizations. You are troubling binaries such as high art and low. You edit the copy and send it back to the publicist.

The publicist does not like your adjectives. He likes powerful. He likes redemptive and bracing. He adds coming-of-age and situates the story, such as it is, in the post-Reagan era. You’ve conceded that calling the book a memoir is probably the best way to explain it and, hopefully, sell it. He likes the way you’ve summarized the arc, thanks.

In fact, you have much in common with JD Vance, if not his dreadful book. The two of you were born four years apart in similar circumstances of, if not poverty, unremitting precarity. Your mothers and grandmothers share some important qualities. You both did well in school, attended state universities, and left home to pursue advanced degrees in prestigious programs. You wrote books about your upbringing. But the similarities end where your respective books begin. You and Vance are both troubled by the conditions of the poor, but for very different reasons. His derision is aimed at the trash classes themselves. Yours is aimed somewhere else.

“In particular, I’d like to avoid mention of Reagan and the phrase coming-of-age,” you write to the publicist. Express gratitude for his help with explaining what the book is about.

Your book is not an elegy, quite the opposite. Or if it is an elegy for something, that something is not hillbillies, who are alive and (mostly) well and making interesting art. Unlike certain vice presidential candidates.

It is hard to explain what a book is about because books contain entire worlds inside them. “There is another world. It is in this one.” - W.B. Yeats. You’ve never read Yeats, but a colleague kept this quote on the wall in her classroom. You both taught 10th grade English. That’s in the book, too: teaching English.

While helping you revise your terrible copy, the publicist wrote that your book is “An indispensable meditation on poverty and art, and a compelling corrective to conventional memoirs about overcoming disadvantage.” You couldn’t have said it better yourself. In fact, you didn’t.

Speaking of adjectives, certain vice presidential candidates wrote memoirs that are ugly in every sense: artless, cruel, unforgiving. But, you must admit, the book has a clear narrative arc. It has focus.

It used to go like this: “The book is about trash.” What do you mean? “I don’t know yet.”

You ask one of your smartest friends, one who is familiar with your work, what your book is about. You take notes when she answers. You copy her words verbatim. You try them on later and they fit like someone else’s shirt.

Vance’s book is a rags-to-riches story. Yours is more like rags-to-, well, better-rags.

Take a call from the publicist while you are at the park. You are supposed to be feeding the hungry. Instead you talk for forty-five minutes about selling your book. From a bench, you watch your friends slice donated bagels and pour iced coffee into plastic cups. “I’d rather not do readings. Nobody likes them, and my friends can only take so much.” Say that. Fine, he says. He’d like to know what you think about creating some video content and whether you are open to getting on TikTok. He will send you a standard Q&A. One of the questions will surely be: What is your book about? “It’s worth putting time into thinking about this,” he says.

The book is a memoir in that parts of your life are in it.

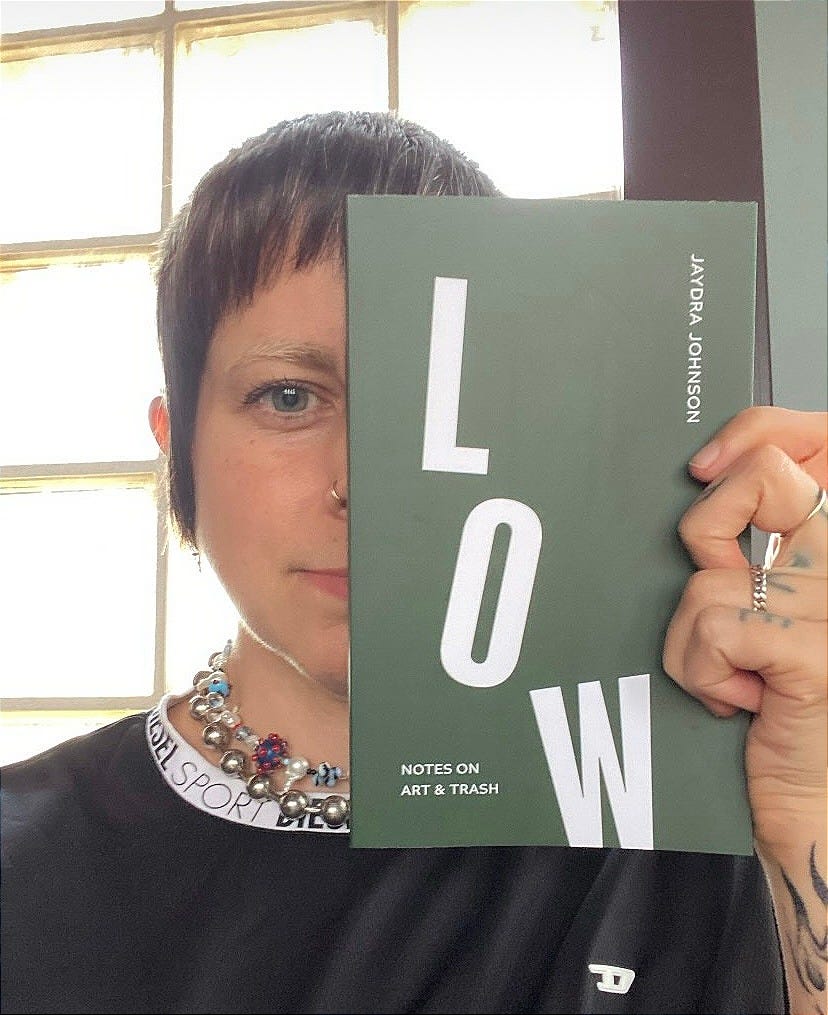

Thank you as always for reading! Although my awful promotional copy has not yet been updated, you can preorder the book here and decide for yourself what it is about.

Fking thrilled for you, Jaydra. Also thanks for this wry bit of prose today.